Jameson Distillery Bow St. Tour

Richard shared his experience just over six years ago here, and while it doesn’t sound like much has changed, I did want to highlight some of the differences and high points.

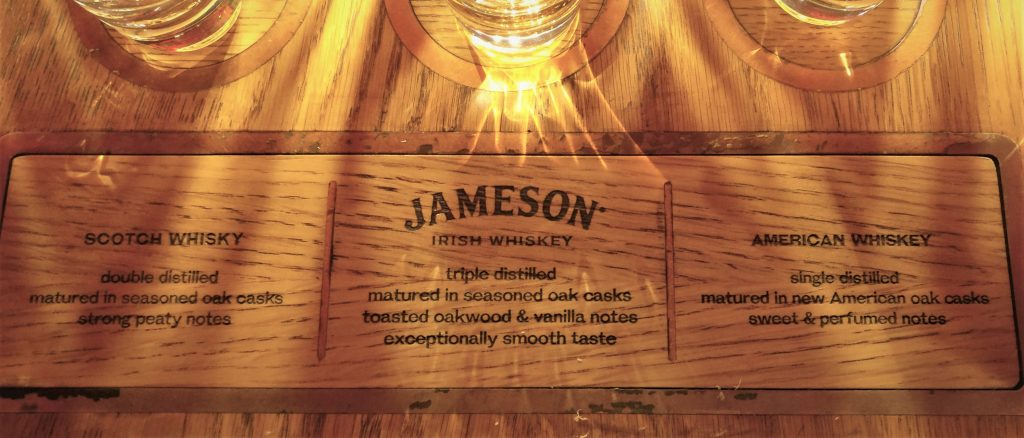

First key change from 2012 – the ticket was €13 and included 1 Jameson drink, while only a few select guests were asked to taste Jameson against an American whiskey (Jack Daniels) and a Scotch (Johnnie Walker). In 2018, the ticket is now €20, but everyone gets 1 Jameson drink AND the opportunity to taste the big three. Is it worth €20 (or $23 USD at the time we were there? To each their own (we weren’t disappointed, but I’ll share a tip to consider at the end!)

Another change from 2012; the only operational distillery offering public tours was Bushmills. In 2018, there are two other distilleries right in Dublin: Teeling Whiskey Distillery (began distilling in 2015) and Pearse Lyons Whiskey Distillery (which opened in July 2017, but Pearse Lyons began distilling a few years prior). So if you’re looking for operational distillery tours, there are many more options today! We did the Teeling Whiskey Distillery tour at the end of our trip, and I’ll share that experience later.

I agree with Richard that if you’re well versed in how whiskey is made, the tour is unlikely to break new ground. This isn’t an operational distillery today, but I thought they did a good job as they tried to lay down now only the process, but make it sensory interactive. First – you can get your free Jameson drink before OR after the tour. Arriving early, we opted for before, and the choices were either neat, on the rocks, or in a cocktail (which I didn’t get the details of, but it involved ginger ale and my Dad thought it was pretty good). These were all premade/prepoured, and you handed them your stub and took one.

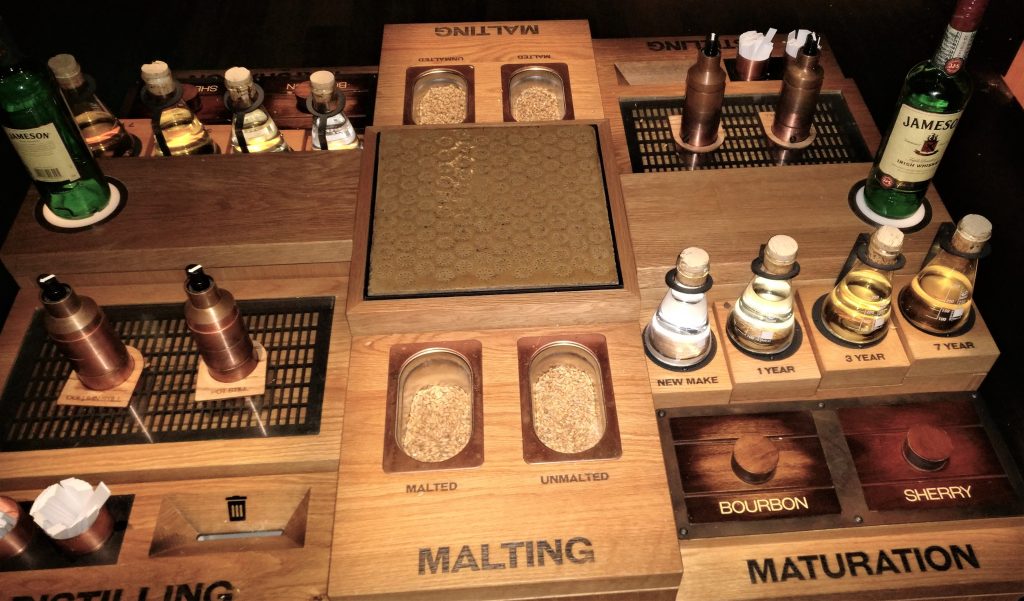

After a short history lesson and a video, the guide takes you into a room where you have groups of 4 at a workstation where they’ll walk you through the whiskey making process.

These nifty workstations are in a fairly dark room, and each has focused lights above it that will highlight the area that the guide is talking about. They start with malting, and highlight the tile in the middle (from a malting room floor), and have malted/unmalted barely that you can feel/smell (I guess taste, but who knows how many folks have fondled it; and the guide didn’t suggest this). Then they move to distillation, where they have a spritzer bottle of spirit produced from a column still and a pot still, and invite you to spritz a long piece of paperboard (think ‘perfume sample’ in a department store) and smell the difference. Then, they talk about the maturation process on the right, with bottles showing the color progression, and small boxes where you can uncork and smell the difference between a bourbon cask and a sherry cask. All in all, I thought it was fairly well done – and for folks who aren’t familiar with whiskey making, probably fairly educational.

Then we get to the good part – the tasting. Everyone gets 3 pours in front of them, and they’re labeled simply “Scotch Whiskey”, Jameson, “American Whiskey”. He has everyone nose the Jameson first and talks about what most experience. Then he has everyone take a wee sip just to prime the palate. He has everyone then nose the American Whiskey and asks if folks can guess what it is (Jack Daniels). Then he does the same with the Scotch Whiskey (Johnnie Walker – I thought Red but couldn’t swear to it). This exercise was to highlight how Jameson compares to the best selling American Whiskey and Scotch Whisky on the planet. We didn’t get any certificates or anything, but it was an enjoyable tasting.

After the tasting, you are customarily ushered through the gift shop, which had a nice assortment of stuff.

A little background – during our trip to Ireland, I was on a quest to find a bottle of whiskey that met certain criteria (listed in order; I was willing to give up the last couple)

1. Something I could afford (wanted to stay under $200)

2. Something I absolutely loved.

3. Something I could not purchase back home.

4. Something non-chill filtered.

5. Something bottled at cask strength.

6. Something distilled/matured in Ireland.

Hence, I was willing to bring home a fine, independent bottling of Scotch if I found one at a shop – provided I could try it first to check off that 2nd box. Nothing in the gift shop jumped out at me, but in the bar area, we noticed that they had a “fill your own bottle straight from the cask” setup which was intriguing. For €100, you could fill your own bottle of cask strength (I’d assume non-chill filtered) Jameson Black Barrel. That definitely checked some of the boxes, and when we asked if we could buy a sample at the bar, they obliged (which gave us a chance to check every box!) My Dad and I shared the pour (a standard 35 mL pour) and gradually added water as we went. The barrel was about 60% ABV, and my guess is that somewhere close to 50% it really hit its stride. Delicious for sure! My challenge was that while delicious, it wasn’t tremendously complex (and while non-age stated, it is likely 7 yrs old or so). Also, this was only the second full day in our 16 day trip. I made a note that if I didn’t find anything I liked better, I’d probably talk myself into a bottle of this.

So – what tip might I offer to those who are familiar enough with the whiskey making process? I’d still pay this a visit if you have the opportunity, but I’d skip the tour all together and go right to the bar and order a pour of the cask strength Black Barrel (be sure to specify that you want to try what they’re selling at that time!) You might be impressed enough to leave with a pretty unique bottle, and one you’ll hopefully enjoy.

Sláinte!

Gary